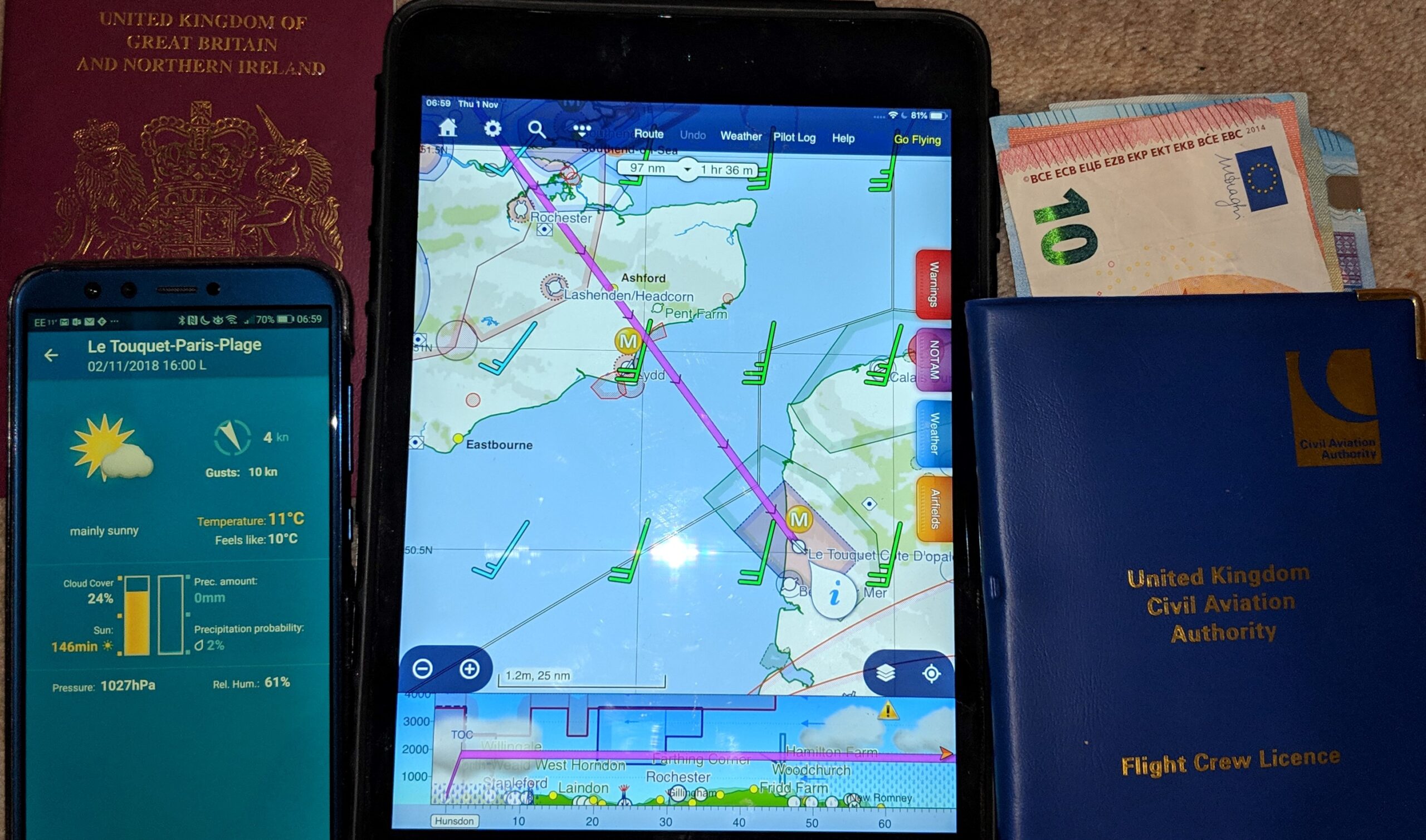

First flight to France – what you need to know

November 1, 2018

A magical mist-ry tour: a cautionary tale

November 30, 2018A perspective on runways

Runways. Fat ones, thin ones, long ones, short ones, hard ones, soft ones, uphill and downhill, even banana-shaped ones. They come in all shapes and sizes, just like the pilots that land on them.

Each one presents a different challenge too. These will be most apparent depending on the airstrip where you trained – if that was a long wide tarmac runway, you will find a short narrow grass strip more difficult, and vice versa. It’s all in the perspective you are used to. I work hard to avoid the classic mistake of rounding out too high on a wide tarmac runway as I’m used to a narrow grass strip and the visual clues I normally get regarding my height are not valid in a sea of grey. It is generally also easier to judge height on an uphill runway, rather than a downhill one where the ground is falling away from you and the runway is shorter than it looks. That’s the reason an airfield’s preferred runway will usually be the uphill one, but that doesn’t always hold true either. I flew in Devon where the pilots preferred hopping over a hedge onto a wet downhill slope rather than the awkward dogleg approach over the village to land uphill.

It’s a good idea to study the plate, which gives you width, length and orientation, alongside a satellite view of the area. A fellow pilot who sketches his own plates for each trip always adds the position of the windsock and control point – vital clues to help you land at an unfamiliar airfield. The satellite image will give you important information about the obstructions you will face – the almost obligatory pylons for any farm strip and the surrounding habitation that often results in noise-sensitive areas to avoid.

When calling for PPR – always wise to do – it’s also a good idea to ask for local knowledge that will help you. There are bumps and dips that those who fly there know about. You can find out where to land long to avoid the bump that will throw you up again on 24 if you come in too fast. Perhaps you can see there is a concrete path crossing the runway at Nuthampstead, or a displaced runway at Cromer, but you need someone to tell you that you should land long at Audley End to avoid the rotor off the trees or what is fondly termed the hippo pool at Rayne Hall Farm. Or even that the pylons at Stoke are simply a visual distraction to be discounted in your approach.

Make sure your airfield information is up to date, particularly with the changes to radio frequencies this year. You will need to know the airfield altitude, circuit height, whether it is left or right hand and joining procedures – but that is for another post entirely!

Many airfields vary enormously depending on the season and surrounding crops. For us in high summer the rape seed plants were almost clipping the wings, adding massive turbulence on one side of the approach, while the winter aspect is a barren field. Similarly, there are times the triangular runways at Sutton Meadows etch a bright number four from the air, and other times you only know the field is there because of the surrounding landmarks.

At large airfields like North Weald or Duxford, one has the option to ask for the grass runway, rather than tarmac. In winter, that may be too waterlogged, but on the grass, it can also often be difficult to distinguish where the runway begins and ends. I recall a friend landing at North Weald and bringing the aircraft to a sharp halt, before exclaiming in surprise: ‘I didn’t realise I could have carried on over the cross taxiway!’

It’s all about perception, and that can change dramatically on the same runway between morning and sunset. Even in the late afternoons in winter, with the sun low and in your eyes, a runway you know well can seem a strange beast and throw you different signals as your gaze moves from crossing the threshold to the end of the runway and touchdown. If you are flying at dusk, your depth perception goes completely, and you will need to rely on peripheral vision to get down. But that’s the fun of flying, isn’t it? Nothing is ever the same.